A week is a very long time in politics in the middle of a campaign about nothing other than the collective desire to kick out the Tories. Months stretching into years have passed in which sage commentators have earnestly decreed that, unless Labour starts to excite the populace, then their electoral performance will suffer. It doesn’t look like it yet. This is a two horse race in which one of the pair must win. If one horse is lame the other wins, irrespective of how excited we feel about it.

The incentive is high for the Labour party to sit tight, to refuse to interrupt the Conservative party while it makes a series of colossal mistakes. Labour could well be on its way to a lukewarm landslide. The metaphor of the landslide suggests the ground giving way, a rockfall, a spectacular collapse as erosion defeats the land mass, hydrostatic pressure opening the cracks in the stable ground beneath. It sounds exciting and invigorating and it tempts us to think that there must be a great deal of corresponding enthusiasm for the landscape that then forms. But the landslide is a collapse. It describes the old falling away, not the new coming into place.

It is therefore quite possible that the nation is so sick of the Conservative party that it will inflict upon it a drastic defeat but that the landslide is not simultaneously a vote of enthusiasm. This would be a rare, perhaps even a unique, event. At previous elections, when one party has fallen apart (1979 and 2019 for Labour, 1997 until 2005 for the Conservatives), the other party has appeared ready for office. The old was ushered out and the new was welcomed in. 2010 was also an easy election to explain as it was marked by a loss of faith in the incumbent but continued doubts about the replacement. The Tory victories of 1992 and 2017 were similar; no love of the status quo but not enough of a warrant for change.

The election we are in now is nothing like this. The closest comparison may lie with 1955. That election, called by Anthony Eden after the retirement of Winston Churchill, was a dull affair. The result was a 60-seat majority for the Conservative party over a Labour party made up of warring disciples of Nye Bevan and Hugh Gaitskell that had been presided over too long by a weary Clement Attlee. Only 25 seats changed hands. The Tories won handsomely — but with no display of enthusiasm.

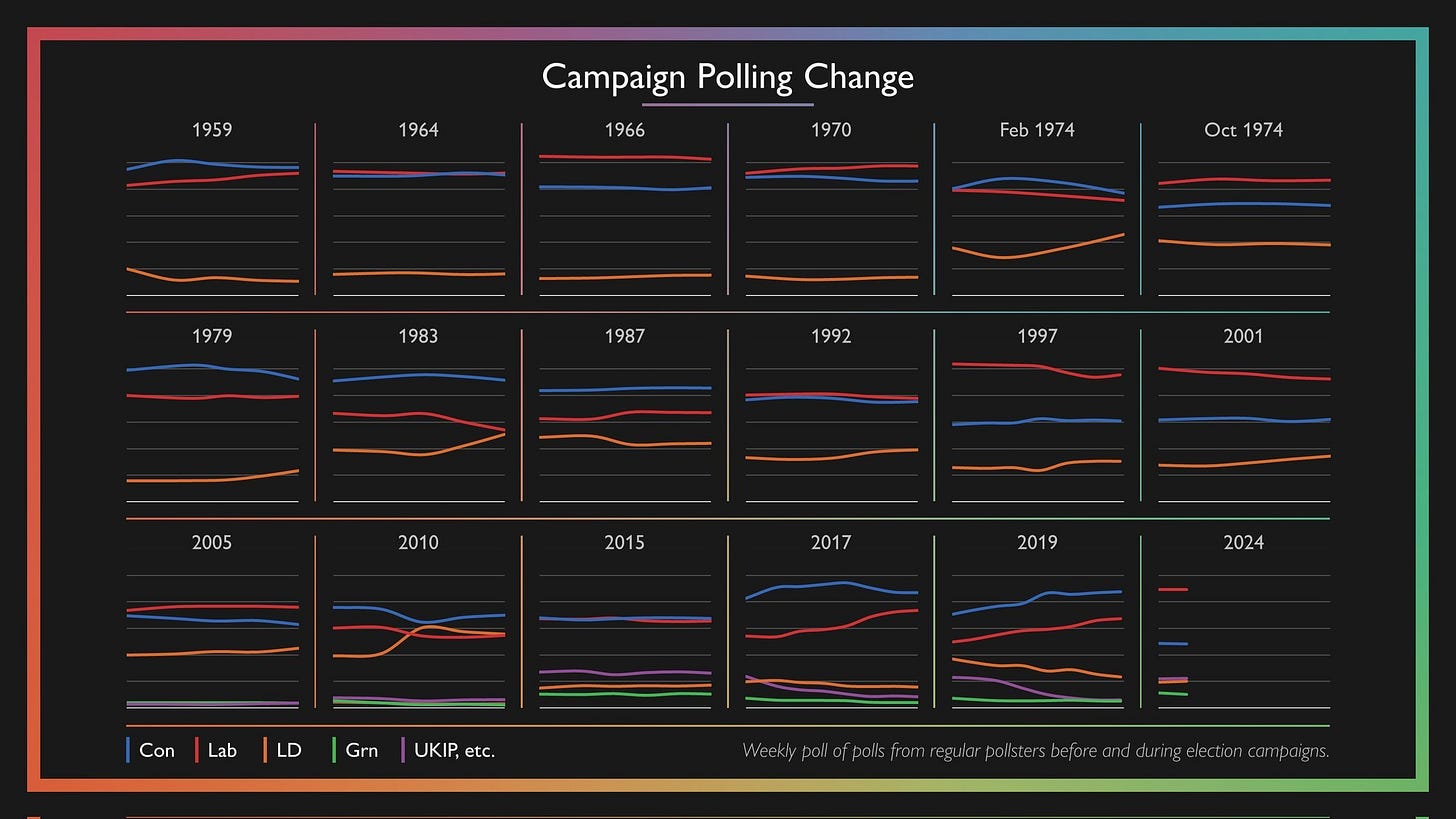

That said, the comparison does only go so far. The Tories extended their lead in the 1955 election. It was not an example of an opposition winning a lukewarm landslide to take office for the first time. Sir Keir Starmer is, in this sense, a pioneer and my strong sense that the election is all but over is confirmed by the chart below. This is a graphic illustration of how little a campaign usually matters.

The preponderance of flat lines shows that the campaign rarely shifts opinion. Even when people have yet to make up their mind they do not do so, as a rule, on the basis of the campaign itself. A good campaign is not a separate event, it is an aide-memoire. It serves to remind the electorate what is bad about your opponents and what is desirable about you. It is a moment at which the big events of the past are dramatized.

The two partial exceptions to the rule of the campaign not mattering appear to be the last two elections, 2017 and 2019. There is at least some movement there. But look closely and you notice there isn’t very much to explain. In 2019 both of the two main parties went up a little as the electorate divided over the question of whether to get Brexit done and the smaller parties were squeezed as a result. The 2017 election is a more intriguing case. Note that the Tory vote fell a little but really not by very much. This flies in the face of the conventional wisdom that Theresa May’s social care announcement almost lost her the election. In truth, it didn’t. The Tories ended up polling more or less what they were polling on the day of the announcement. The big shift is in the Labour vote. The rise in the Labour vote in 2017 is the one great unexplained event. Rather like Leicester winning the Premier League and thereby keeping up the illusion that it is a competitive league, this is the moment that keeps campaigners knocking on doors. Yet surely 2017 is an outlier. The desire to punish the government over Brexit and austerity coupled with the notion that Labour could not win and that therefore the risk of a Corbyn premiership was slim probably crystallised a late vote. There were so many people who doubted what they might do but in the end they all broke Labour. Probably. As I said, it’s not obvious.

It is, however, the exception and certainly nothing comparable has happened in this campaign yet. The running average of the polls, at the start of this campaign, had Labour on 44 per cent, the Tories on 23 per cent, Reform on 11 per cent and the Liberal Democrats on 9 per cent. It will be worth watching whether anyone moves. The last poll just before the time of writing this post gave Labour the same 21 point lead. It’s enough for a landslide, lukewarm or not.